Could 3D printed boats become the next big trend in boatbuilding? Vasileios Sofikitis explains all…

You are at home, sitting at your desk. In front of you, on your laptop, is a bespoke 3D rendering of the boat you’ve just finished refining online. You lean back gazing admiringly at your design. The detailed online forms took you a couple of days to fill in but the result looks exactly like the boat of your dreams. OK, time to print it out.

Wait, what? It reads like a scene from a sci-fi novel but this might well be the reality of how we will all go about buying and manufacturing boats in the not too distant future. The current GRP boat building procedure is a complex, time-consuming and expensive process with limitations on the type of shape and structures that are achievable.

It usually starts by handbuilding or milling and fairing a perfect full size model from which the female moulds for the hull and deck can be created. These moulds have to be carefully aligned, reinforced and waxed before the gelcoat and multiple layers of glass matting and resin can be added.

Article continues below…

Sharrow MX-1: This toroidal boat propeller could be top of the props

Welcome to the future: 5 futuristic yachts being built today

This then needs time to cure at a precisely controlled temperature before the hull and decks can be removed and the whole cleaning and waxing process starts again. But this won’t be the process for much longer if the latest advances in 3D printing are anything to go by.

Meet MAMBO (Motor Additive Manufacturing Boat), the world’s first 3D printed fibreglass boat. It was launched by Moi Composites at the 2020 Genoa Boat Show in October. The Italian start-up drew inspiration from the Arcidiavolo design of British power boating legend Sonny Levi.

They spent almost six months running hydrodynamic simulations on Autodesk’s cutting-edge design and simulation software to refine Levi’s multihull before settling on a final design that takes full advantage of 3D-printing’s capabilities.

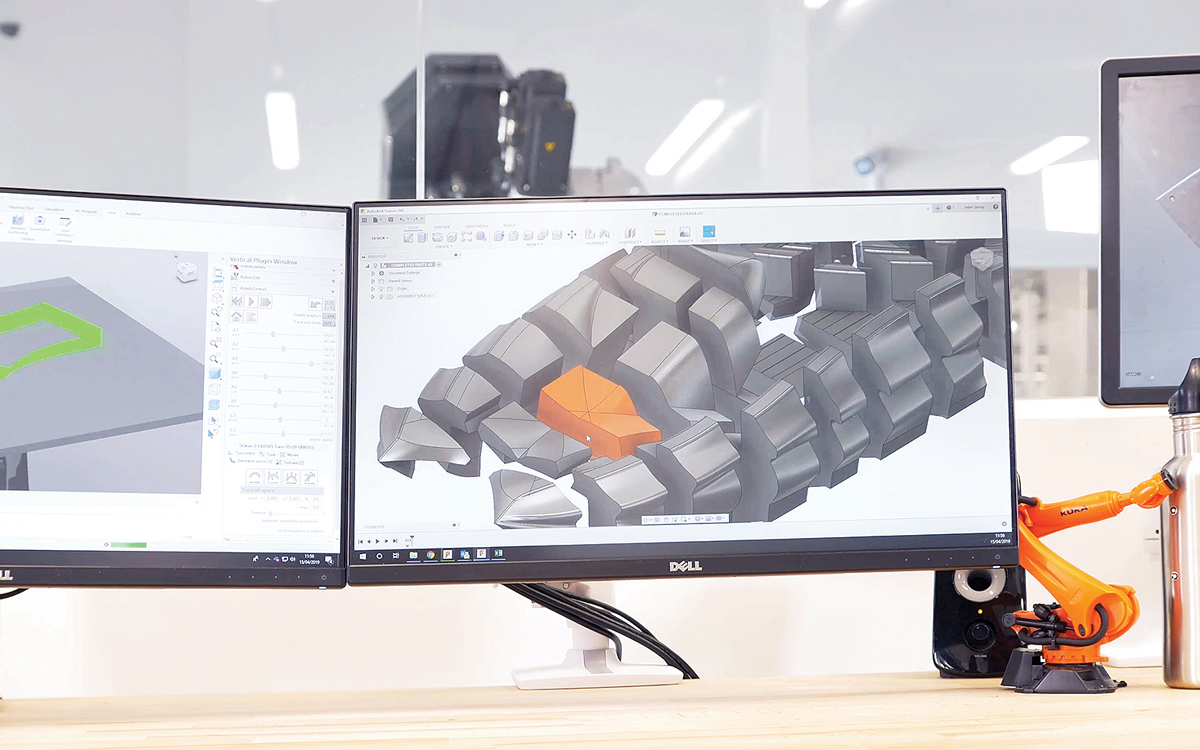

Software breaks the shape into printable sections

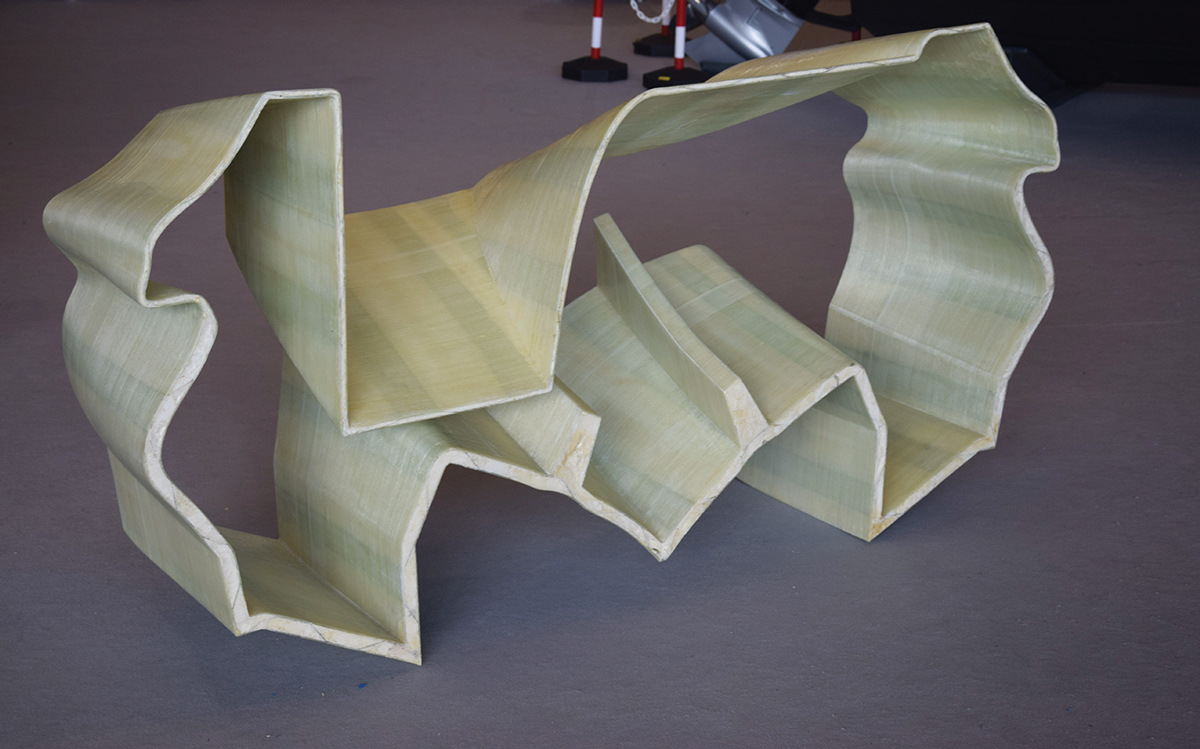

As a result, MAMBO sports some very unusual design ideas both above and below the waterline that simply wouldn’t be possible with the limitations of the moulding process (you have to be able to remove the moulding without destroying the mould).

MAMBO features a radical three-pointed hull featuring an asymmetrical deck layout and intricate organic forms that play a role in both its aesthetics and structural integrity. It measures 6.5 metres long by 2.5 metres wide and has a dry weight of just 800kg.

A relatively modest 115hp Mercury Pro XS outboard engine provides the power. The aft bench, the shape of which resembles a baby grand piano, is a reference to Mambo, the Cuban musical genre. These unorthodox design solutions not only help differentiate the boat from other craft on the water but also showcase the seemingly limitless possibilities offered by 3D-printing.

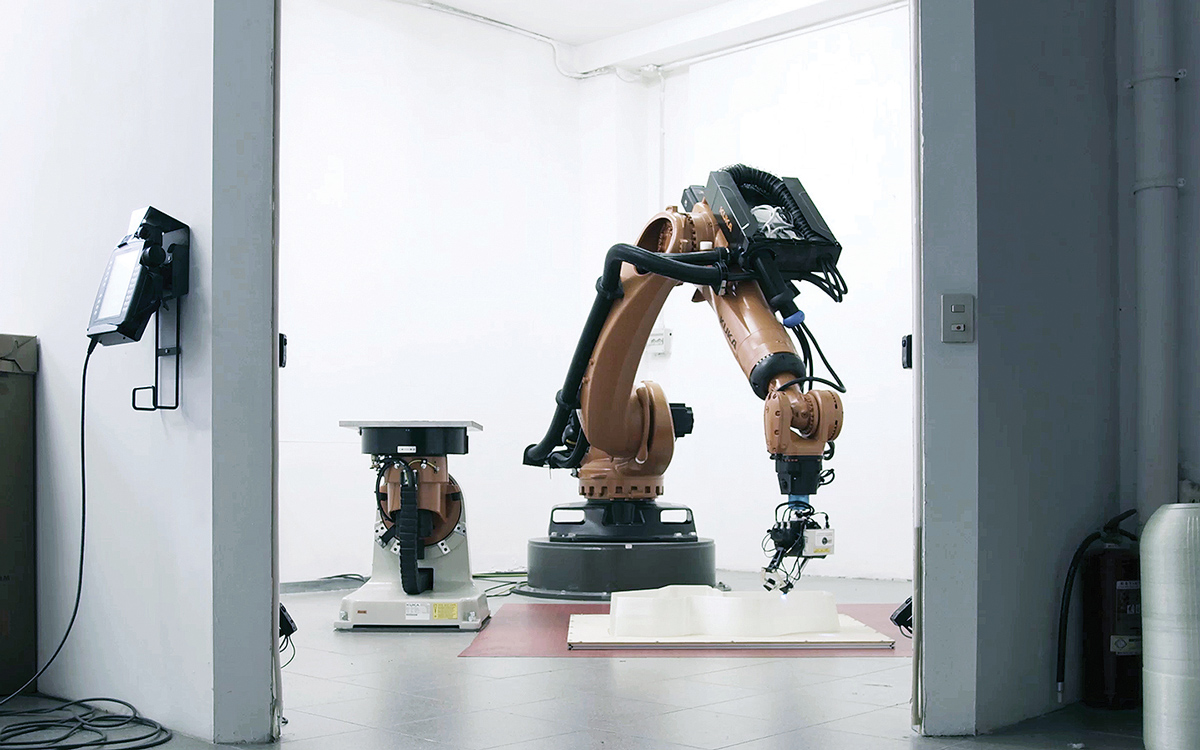

A robotic arm prints out each segment using a continuous glass fibre filament impregnated with thermo-setting resin that cures instantly

In order to print MAMBO, Moi employed an innovative, remote cloud-based workflow process that helped leverage the best talents and facilities around the world. Two separate printers, one in Moi’s headquarters in Milan and the other in Autodesk’s manufacturing facility in Birmingham, UK, jointly produced MAMBO’s components, demonstrating another advantage of 3D-printing — decentralised manufacturing.

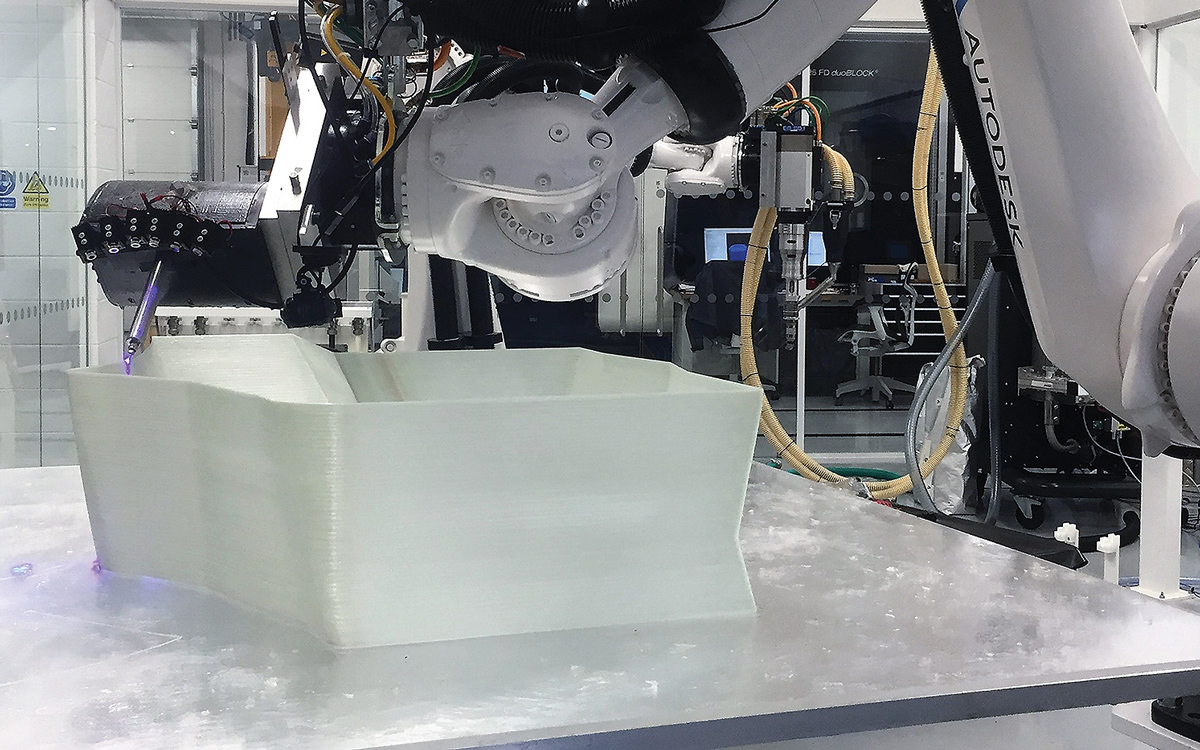

MAMBO’s greatest innovation however, lies in its 3D printing technology. It uses a patented process known as continuous fibre manufacturing (CFM) that extrudes a continuous stream of glass fibre infused with thermosetting resin, which instantly cures under the printer’s UV lights.

This continuous glass filament creates an immensely stiff structure, resulting in a much lighter but more durable hull. The use of CFM minimises waste, enhances precision, and enables the creation of shapes that would be impossible or prohibitively expensive using traditional methods.

By repeatedly going over and over the previous layer it slowly builds up into a single finished 3D shape that is lighter, stiffer and more complex than a conventional GRP moulding

Once printed, MAMBO’s components were sent to Catmarine’s shipyard in Miggiano, Italy, for final assembly. Here the different sections were laminated together using glass fibre matting and polyester resin and painted electric blue. The deck was covered with eco-friendly cork and its seats upholstered in white leather.

MAMBO suggests that 3D printing will appear first in smaller sportsboats and day cruisers. As printers become larger and quicker though, we could start to see bigger boats manufactured in this way. 3D printing is already being adopted in other industries as an alternative to the traditional, more expensive methods of lost-wax casting or plastic moulding, especially for complex shapes and small production runs.

Many boatyards are also starting to use 3D printing for low-volume parts and rapid prototyping applications.

The individual sections were printed at two different facilities in the UK and Italy

Even boat owners wanting custom pieces or replacement parts that are no longer available are starting to look to 3D printing as a solution, with companies being set up to answer this demand. The Italian firm Superfici exhibited just such an example of their work at Genoa, an innovative steering wheel design prototyped on a 3D printer.

There are still some limitations to 3D printing when it comes to the size, cost and scalability of large items such as boats. The assembly of many small components and the need for post print processing pose a challenge. The variety of materials used in boat-making, such as wood and stainless steel, neither of which are yet printable, also present problems. However, projects like MAMBO prove that most of these problems will eventually be solved.

When projects like MAMBO start to lure boat builders into the realm of 3D printing and how that will coexist with the art of traditional boat building, remains to be seen. However, the recent addition of glass fibre to the repertoire of 3D printing materials is certainly going to be a boon for recreational boaters.

Designs that are currently restricted to a virtual world of CGI renderings due to the difficulty of making them using conventional moulding techniques will soon become viable, opening up a world of new possibilities and disrupting boat building as we know it. The big question now is whether we, as consumers, are ready to press print.

First published in the February 2021 issue of Motor Boat & Yachting.

These sections were laminated together by hand

The completed boat gets a final spray paint