Philip Davies and Nigel Boutwood tackle the most challenging leg of their circumnavigation of Great Britain – along the exposed north coast of Scotland

This is part four of Phillip Davies and Nigel Boutwood’s round Britain adventure. You can read part one here.

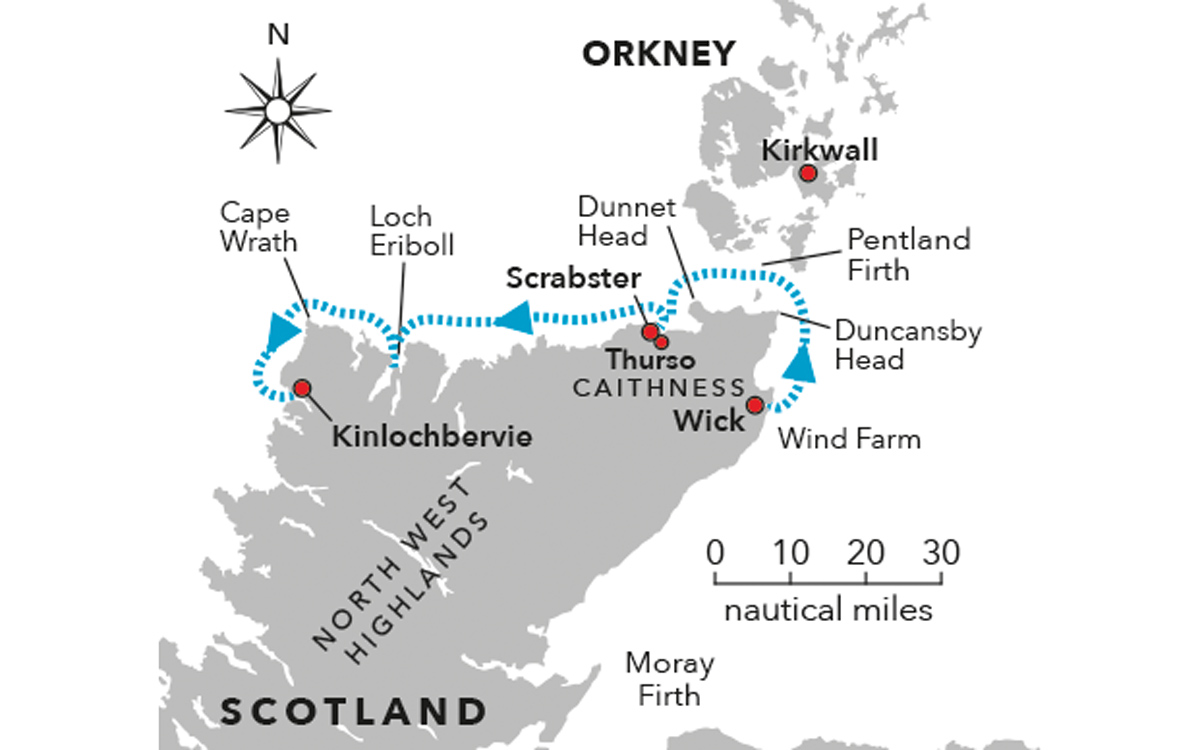

The most daunting day yet of our attempt to circumnavigate Britain in my tough but small 27ft Rhea has arrived. We have made it to Wick at the north-east tip of mainland Britain, but ahead lies the perilous journey along the exposed north coast of Scotland via the feared (and only to be attempted in ideal conditions) Pentland Firth.

If we make it through this infamous strait that separates Scotland from the Orkneys unscathed, we will eventually be confronted by the even more ominously named Cape Wrath at the far north-west corner of Britain.

Since the fateful night that we decided to undertake this adventure back in the autumn of 2018, I have been constantly tracking the coastal and inshore forecasts for this stretch. Not once have I seen the sea state ‘smooth’ appear in the forecast and only on a couple of occasions has ‘slight’ made it on to the page.

On the other hand ‘moderate to rough’, ‘rough to very rough’ or simply ‘high’ seem to appear with almost monotonous regularity. No wonder I have spent most of the last six months falling asleep thinking about this leg and then waking up having nightmares about it.

This morning is no different except that now the day of reckoning has finally arrived. Not that Nigel seems to be too fussed about it judging from the snores still emanating from his berth.

Wick to Scrabster

Before leaving, we need to stock up on provisions just in case we get holed up for a few days in a place called Loch Eriboll, the only designated ‘port in a storm’ near the Cape Wrath end. The only problem is there are no shops, pubs or civilisation of any kind nearby; we will simply have to anchor and fend for ourselves until the weather blows through.

Article continues below…

Cruising around Britain in a 27ft boat: Part 1 – Gosport to Ramsgate

Firth of Clyde: Spectacular cruising on Scotland’s west coast

I ask a local boat owner where the nearest shop is and he recommends Tesco out of town. It’s too far to walk so he offers to drive me there, wait while I fill my basket, then drive me back again. I accept this very kind offer.

On the journey to the shops he reveals that he’s 87 years old and his boat, a rugged locally built 20-foot single-engined fishing boat, is 45 years old. Both seem to be in very fine fettle for their age. I tell him we’re just about

to go around the top and he confirms that he thinks it’s a good day for it. I am more than a little relieved that this man of considerable local experience approves of our timing.

Having completed the shopping trip, I make a more than usually fastidious check of the engines, which also appear to be in fine condition. Then I fire up the Nespresso machine, approximately 3ft from Nigel’s snoring head. It does the trick and wakes him from his deep slumber.

On his way to the shower block I give Nigel the task of asking the harbourmaster where the diesel pump is and whether he thinks today is a good day to tackle the Pentland Firth. On his return Nigel informs me that diesel isn’t available for pleasure craft as the pump is only designed for big commercial trawlers that take thousands of litres at a time. We’ll have to call in at Scrabster, 20 miles or so west of the Pentland Firth.

As in Peterhead the harbourmaster kindly agrees to donate our berthing fee to our charity fundraising instead. Thank you very much, Wick Marina. He also drops by to give us a course to steer through the dreaded Firth that will help us avoid all of the nastiest bits. The plan is to get to Duncansby Head by 11.30am to catch the most favourable tidal conditions for the eight-mile transit. We leave without delay.

The sea state is slight and on our starboard beam as we cruise up to the very top right-hand corner of Great Britain before cutting in close to Duncansby Head as we make the second of our very significant left turns since leaving Portsmouth.

A left turn at Duncansby Head leads the duo into the mouth of the notorious Pentland Firth

With the sea state now gently following us, we stay close inshore for a few miles before turning to the north-west, south of Stroma island, to avoid the worst effects of the fearsome tidal race around the rocks known as the Merry Men of Mey.

The Pentland Firth itself is the stretch of sea between Dunnet Head and Duncansby Head on the mainland and the Orkney Islands. It’s approximately eight miles by five miles and is acknowledged in all the almanacs and pilot guides as one of the most fearsome stretches of sea in the whole of Great Britain.

Most of the advice is written for the benefit of over-optimistic pleasure boaters and particularly ‘rag and stick’ sailors, who might suddenly find themselves going backwards at a rate of knots if they arrive at the wrong time due to a peak tidal flow of 12 knots.

The sea state appears deceptively calm en route to Cape Wrath

Even a sailing boat’s engine is likely to be fighting a losing battle against this kind of flow, culminating in the boat being delivered into the less than welcoming arms of the Men of Mey. Not a good idea.

Not-so-fearsome firth

Thanks to our carefully planned timing and twin 220hp engines we scoot across a perfectly flat sea disturbed only by a series of minor ripples in the ‘race’ part. I have had many a worse moment going into or out of Portsmouth harbour on a spring ebb. After all the countless hours I have spent thinking about this passage, what a pleasant anti-climax it turns out to be.

Once in the clear we call ahead to Scrabster to arrange a refuel. The harbourmaster informs us that the fuel quay doesn’t open on Sunday, but he might be able to get the attendant to turn up if we give him 30 minutes notice. We will have to pay cash, however, as there are no card payment facilities on Sundays.

Scrabster looks a picture of tranquillity in fine weather

We arrive in the basin at low tide to find the fuel pump 20 feet up a nasty barnacle-covered harbour wall. I have visions of Start Me Up’s lovely navy gelcoat being scraped right off but with loads of extra fenders deployed we come tentatively alongside.

Gregor, the Polish fuel attendant, says that I have to scale the ladder to fill in a form before he can pass me the fuel nozzle. Or wait for high tide. Not an option, we have to get around Cape Wrath today and so up I go. Nigel is very concerned for me but even more concerned for himself as if I have a heart attack half way up I will land on him! Cheers Nigel.

I need about £300-worth but only have £100 cash. Gregor offers to take me to a bank in nearby Thurso to get the cash. Whilst driving me Gregor takes the opportunity to let me know what he thinks about Brexit – he isn’t impressed.

Phil scales the rusty ladder up to the fuel dock

On our return I descend the ladder (even more frightening) and Gregor lowers down the incredibly heavy fuel dispenser at the end of a three-inch diameter hose. Then it’s back up the ladder to pay for the fuel and back down again to restart the engines. Who knew boating could be such good exercise? Then on we go.

I had allowed a total of five hours to get from Wick on the east coast of Scotland to Kinlochbervie, 15 miles south of Cape Wrath. This timing would give us the best tidal conditions and sea state to get round the cape itself. We had wasted an hour on the unplanned stop for fuel in Scrabster, so were already behind schedule. Hopefully, the Sea Gods would continue to smile on us as made our way the 50 miles west to Cape Wrath.

Once clear of Scrabster we set a course for Cape Wrath and put the hammer down. The sun is shining and the sea remains eerily calm. Nigel comments that it is the best sea state we have experienced since leaving Gosport. I hope he isn’t tempting fate.

Even from a distance Cape Wrath looks menacing

On the horizon we can see some ominous darker clouds gathering with banks of showers hanging like curtains beneath them. The sea state gradually builds but remains in a favourable following direction. Then 30 minutes later larger white caps start to form and the wind and waves swing round to hit us directly on the bow.

We have got far enough along the coast for the decision to turn back to Scrabster to look less appealing than pulling into Loch Eriboll if things get worse, in the meantime, we slow down to displacement speed and plough on.

With each passing squall the waves get bigger and the gaps between them shorter. After successfully climbing to the top of one we now plough straight into the next one, sending sheets of spray over the wheelhouse. The boat is coping extremely well but I can’t see us putting up with this for very much longer, so we decide to pull into Loch Eriboll a few miles distant to find some shelter from this unpredicted stormy weather.

At the western headland leading to the entrance to Loch Eriboll we turn to port hoping to gain some protection from the huge waves rolling into our starboard beam. It seems to take an age but little by little the waves get smaller and smaller until we are safely in the sheltered water of Loch Eriboll itself.

The loch is almost 10 miles long and has been used as a port of refuge for centuries. The Royal Navy used it extensively during World War Two and it was fondly referred to as Loch ‘Orrible by the British servicemen stationed there.

It is spectacularly beautiful but has nothing to offer leisure boaters other than peaceful anchorages and a lovely view. I am at least pleased to have made that trip to Tesco but still don’t want to be trapped here for long. There is no mobile signal and the feeling of being cut off from the world other than the trusty VHF weather forecasts is disconcerting to say the least.

Over the top

We count three sailing boats anchored in the most favourable spots and chose a spot ourselves to consider our next move. Having successfully dropped the hook we realise that what we thought was a local’s mooring buoy is, in fact, a fisherman’s pot marker with a very long rope attached to another small float.

So we pull up the anchor and look for another spot towards the head of the loch. We’re just about to drop the hook again when I spot in the pilot guide that the weather can be fickle at this end of the loch due to katabatic winds funneling down from the mountains. Not ideal for a peaceful night’s sleep!

We head back towards the entrance of the loch looking for a more favourable anchorage and notice that the wind has dropped. We carry on a bit further and decide to poke our nose back out into the ocean to see if it has reduced to a manageable level for the remaining 30 miles round Cape Wrath to Kinlochbervie.

The view from the pub at Kinlochbervie

We’ve lost another 90 minutes dithering over anchorages, but when we finally exit Loch Eriboll the sea state has reduced dramatically and the stormy weather has passed away to the east so we press on towards Cape Wrath. It looks every bit as severe as its name suggests so we give it a wide berth to avoid the worst of the various tidal races and head south for the first time since leaving Gosport Marina.

I wondered what the sea state would be like round this corner but it is fine and an hour later we are safely in Kinlochbervie, a fishing port with space for eight visitors on a floating pontoon with electricity, water and some great views of its own. There is a hotel with a bar and restaurant, a Spar and a fuel berth – what more could we wish for? The restaurant is a mile away up a big hill but thanks to our newly acquired electric scooters this isn’t an issue.

It’s time to celebrate; we have successfully rounded the top of mainland Britain and are full of a sense of achievement. By the end of the evening we are also full of numerous beers, wine and eventually rum-based drinks. Perhaps those scooters weren’t such a good idea after all.

First published in the March 2020 edition of Motor Boat & Yachting.