Iain Macneil’s round-the-world record attempt continues as the 24m MV Astra rounds Cape Horn and takes on the Pacific Ocean…

This is Part Four of Iain’s round-the-world expedition. Make sure to read Part One, Part Two and Part Three first.

Our passage around the Horn was not destined to go peacefully. We had intended to round the Horn and then head North through the channels to Ushuaia to refuel.

I hadn’t taken on a full fuel load in Montevideo in case seas were lively at the Horn, so it was essential to stop before the 1,800nm leg to Valparaiso.

However, as we approached Cape Horn, the lone lighthouse keeper (a Chilean Navy appointment, usually married with children) called us by VHF saying we could not enter Chilean territorial waters. I suspected this may be due to ongoing friction between Chile and Argentina over border disputes.

Unable to take the route we wanted to, the only option remaining was to double back 80 miles and head 60 miles along the Beagle Canal from the East to Ushuaia before heading back south to Cape Horn. The channel itself was a calm run, very similar to the Sound of Mull!

Article continues below…

Around the world in a 24m boat: Part one – How Iain Macneil found MV Astra

Around the world in a 24m boat: Part two – How Iain Macneil refitted MV Astra

Day 46: 15 Jan

We needed a pilot to enter Ushuaia as we were instructed to moor at the cruise ship berth. In summer this is heaving with cruise ships heading to the Antarctic but at this time of year it was empty.

Once secure, a team of three divers arrived to check our propeller was undamaged by whatever it was we’d picked up on the previous leg. Thankfully, it was all fine.

A weather system was rapidly developing to the SW with winds gusting over 50 knots so I decided to stay in Ushuaia for three days to refuel and wait for a weather window to head back down to Cape Horn.

Astra’s aft crane came in handy for lowering stores from Ushuaia’s cruise ship terminal

Once round it we would need to get sufficiently far north on the western side before the next storm arrived. Our Chief Engineer, Paul, used the time to deal with some of the maintenance that can only be done when the engine is off.

Our list of priorities had changed because the diesel we took on in Montevideo was contaminated with globules of heavy fuel oil and was fouling our filters.

After changing the Racor Filters and cleaning the fuel oil purifier, Paul transferred the balance of the contaminated fuel back to the tote tanks on deck – we really didn’t want to be running on dirty fuel when we were at our most exposed rounding the Horn.

Iain fills in yet another set of port papers

Instead, the plan was to use it once we were back in better conditions but before we reached Valparaiso. The last thing we wanted was to be relying on this contaminated fuel to make our way across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

Day 49: 18 Jan

Gusts exceeding 50 knots were whipping across the bay and while our anchor was well bedded in, I put out 70m of chain to give us a longer lead.

As planned we set off again at midday to round the Horn, which is not considered complete until you cross the parallel of Latitude 50° South on the opposite coast.

70m of chain helped secure Astra against the 50-knot winds in Ushuaia

We finally achieved this on 23 Jan, 11 days after our first attempt. Even then we ran into a second storm after turning to head up the coast. Battling waves up to 20ft high, we had no option but to run with the wind and seas for six hours!

Carrying additional fuel meant crew had to be out on deck attending to fuel valves and operating the transfer pump during gaps in the weather. To counter the freezing temperatures and 35-knot Antarctic winds, they wore insulated wet weather gear, lifejackets, handheld radios and personal locator beacons.

Astra actually came through the storms pretty much unscathed, with damage limited to a few fittings and a couple of the empty tote tanks.

A sleeping whale

Day 51: 20 Jan

While we had been entertained by humpback whales in the South Atlantic, this week we nearly ran down a whale 150nm west of Cape Horn in the South Pacific.

It was a cold day (3°C) with the sun immediately astern of us when Carlos suddenly saw something strange and motionless in the water ahead, just below the surface, like a stationary submarine. Whale! He quickly altered direction, 15° to port, to avoid striking it and narrowly missed the slumbering beast.

As we moved up the western Chilean coast, I kept in deeper water (2000-3000m) to ensure that the wave period was as long as possible, creating a smoother pitching effect and allowing us to continue without losing too much speed.

The crew’s staple diet of meat and potatoes – again!

The weather got steadily colder over the 7-10 days it took us to round Cape Horn and our diet became more carb-heavy as we worked our way through our stock of fresh potatoes.

We finally resorted to the “Neil Armstrong” drawer that contained the emergency dehydrated food and a stash of powdered potato to accompany our Uruguayan meats!

Entering Valparaiso, Chile

Day 59: 28 Jan

We finally arrived at Valparaiso anchorage, where the port health authorities boarded us to take antigen tests and check our food hygiene arrangements.

Chile is extremely concerned about the inadvertent import of bugs and insects so they appreciated our absence of cardboard packaging and the fact that our food had been packed in vacuum bags before leaving Lanzarote.

We had a significant fuelling and stores job ahead of us but it was not until 23:45 before we were called to the Pilot Boarding Station. At 01:06, as we moored alongside we were informed that we had to vacate the berth at 05:30!

Approaching Valparaiso with empty deck tanks

Several van loads of stores were waiting for us but, as our berth was designed for a ship ten times larger, we couldn’t simply pass them onboard and had to use our aft crane to lower them down.

It took nine large sling loads to bring the stores onboard, including an exercise bike we’d bought to help us keep fit.

I had also ordered 34,000 litres of fuel for the Pacific crossing, but when the road tanker arrived it only had 32,000 litres – luckily I had deliberately over ordered a little!

At 05:30 our Pilot was back onboard to accompany us to the harbour entrance. One departure form included questions on the number of days sailing range (50 at economical speeds) and the number of days food onboard (approximately 100).

As we set out from Valparaiso to cross the Pacific, there was a sense that this really was the big one.

We had already crossed two 3,000-mile stretches of ocean but now we had to cross a body of water of 4,400nm in a boat just under 75ft that had to be fitted with fuel tanks on the fore and aft decks to ensure we could make it.

Six of the 14 extra deck tanks Astra carries

Our buying agent, John Clayman of Seaton Yachts in Newport R.I, had said to me “You’ll have to turn any boat below 24 metres into a tanker to get her to cross the Pacific”. He wasn’t far wrong!

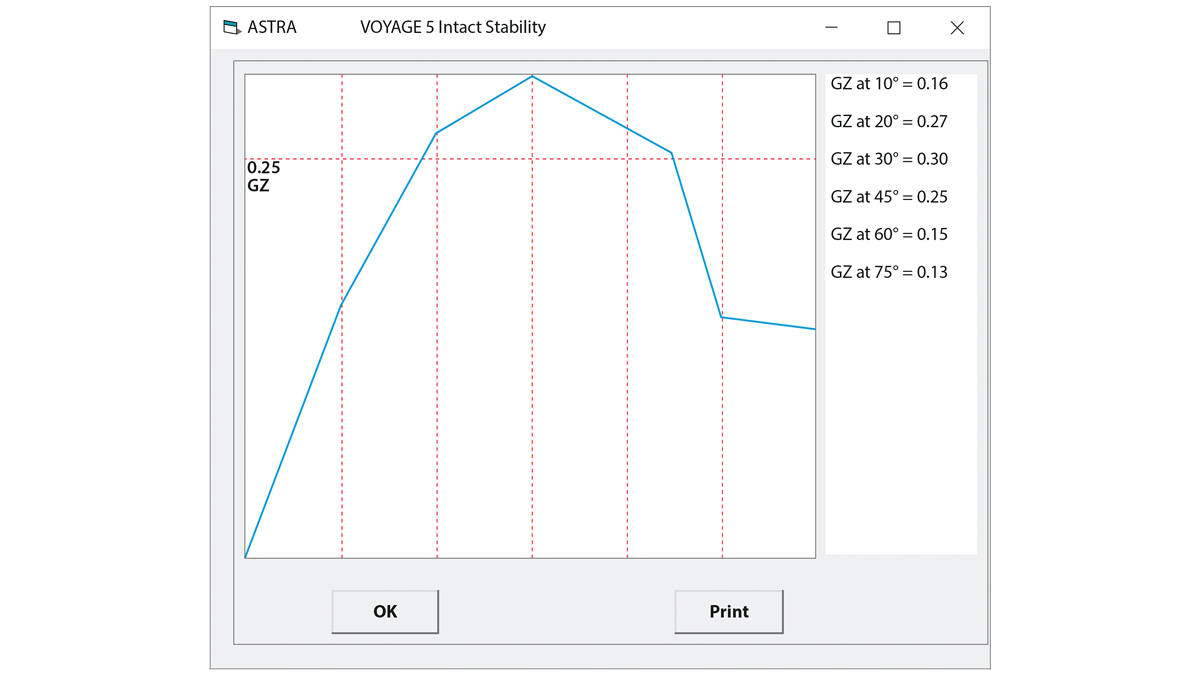

In order to give Astra sufficient range we have no less than 20 separate fuel tanks, a main fuel transfer and stripping pump, two slop tanks (holding 8% of tank volume), a common vent line to all tanks, local liquid level gauges, hydrostatic and electro-magnetic liquid level gauges and a set of reducer couplings for fuel transfer.

Furthermore, all fuel movements have to be checked in the boat’s stability computer before completion – but honestly, it still doesn’t sound like a tanker to me!

After rounding the fearsome Cape Horn and tracking North to Valparaiso the crew had to decide between three possible routes across the Pacific

Our specialist weather router at passageweather.com agreed with our approach of taking a dogleg north across the Pacific to keep us in the main body of the anti-clockwise rotating winds and currents that dominate the Southern Oceans.

I had originally identified three possible routes across:

Great Circle (4,205 miles)

This is the shortest route. However, in the southern hemisphere, the apex of the great circle is quite a way towards the South Pole, which would draw us into opposing winds and currents.

Rhumb Line (4,300 miles)

This is the direct route, on the same compass heading across the Pacific that crosses each meridian of longitude at the same angle. However, it passes through the typical centre of the South Pacific high pressure and could slow our passage.

Dogleg North (4,410 miles)

This route is about 250 miles north of the direct rhumb line route to the main body of the anti-clockwise rotation of ocean currents and will provide us with more favourable conditions.

While this route is 100 miles longer than the rhumb line and 200 more than the Great Circle, 0.25 knots of additional speed would provide both speed and fuel consumption benefits.

To check that Astra had enough range for this, I had created tables and curves of performance that provided firm data against which I checked actual consumption performance every day at 12:00hrs.

The most economical fuel speed setting for Astra is 600rpm with a 60% setting on her variable pitch propeller, delivering a speed of 6.53 knots at a fuel consumption of 28 litres per hour. We need another 3lph for the shaft or Cummins Onan generator, taking it to 31lph in still water conditions.

In open seas of variable conditions, typically 10ft (3.0m) waves with winds up to Force 5-6 and currents, we have to vary our engine speed to take this into account so we usually end up burning between 8,400 – 8,600 litres of fuel per thousand miles (about 8.5 litres per nm).

Therefore, on a full fuel load of 43,000 litres, the extremes of range vary from a maximum of 9,000nm to a minimum of 5,060nm. In practice, we keep 4,000 litres of fuel in reserve, which on the basis of economical steaming would give us another 800nm.

We set off across the Pacific at our most economical engine speed of 600rpm although with a full load of fuel adding 20 tonnes our actual speed was 5.75 knots.

After three days, we increased this to 700rpm (7.3 knots) taking the fuel consumption to 1,000 litres per day.

The only downside of this slow steaming is that we have to periodically de-coke the engine to remove the carbon deposits that build up at these low engine speeds. To counter this, we occasionally increased the RPM and pitch to bring the exhaust gas temperatures up to 350°C.

Once settled at 1,000 litres per day, the strategy was to run for three full days to get an accurate set of figures, while maintaining our reserve of 4,000 litres. With every passing day, the weight carried also reduced, so we were a little faster each day too.

Day 70: 8 Feb

Today we increased the engine speed to 750rpm and the pitch to 71.5% making a speed of 8.3 knots and covering 200nm per day. Back in January I had estimated that it would take us at best 23 days to cross the Pacific and at worst 27 days, so we based our ETA on 25 days.

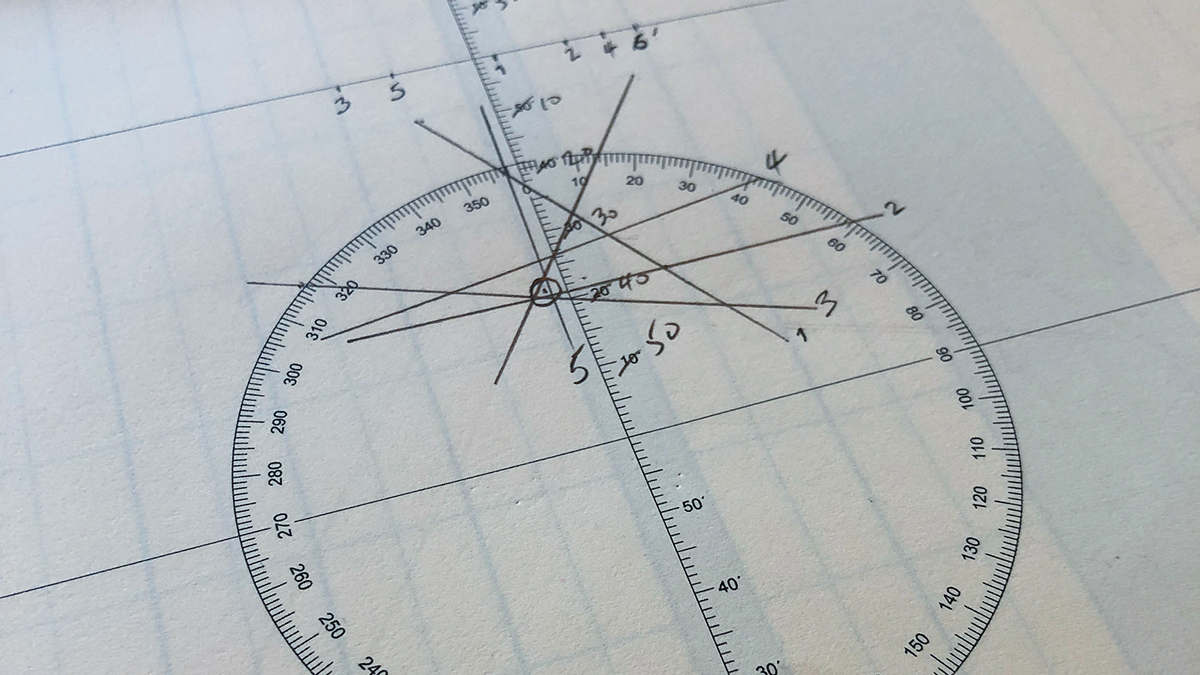

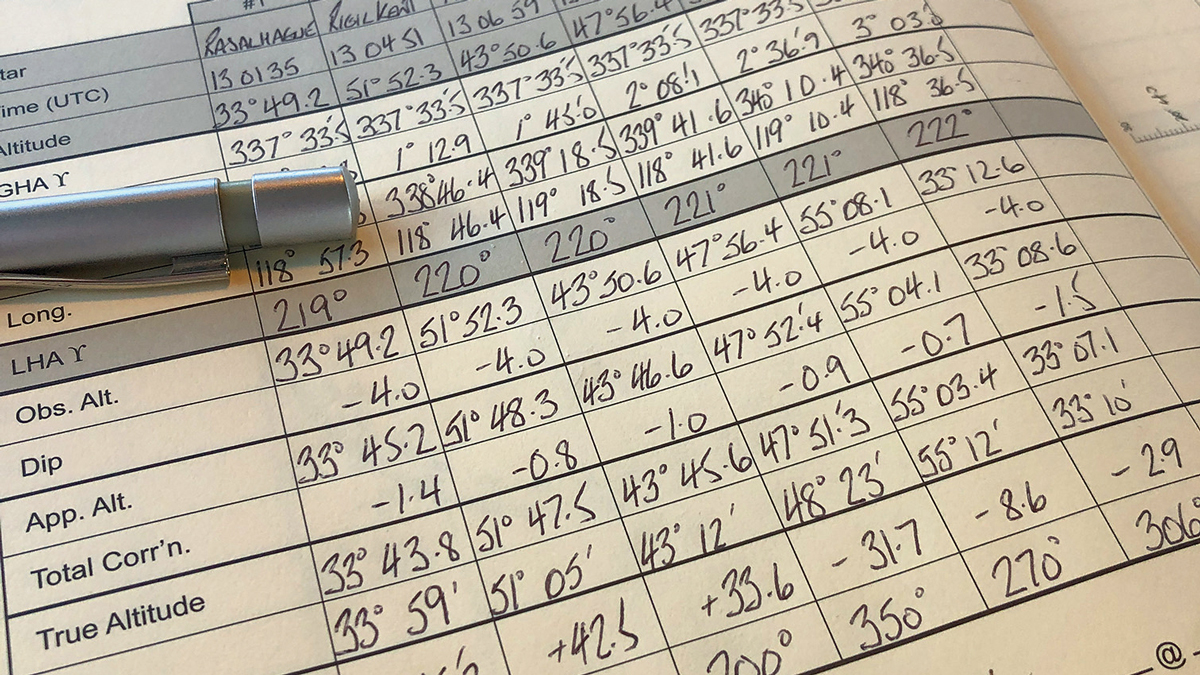

The crew used the long Pacific crossing to practise celestial navigation while keeping a close eye on fuel consumption

We saw very little other traffic during our crossing. There are three radar sets on the bridge, the most powerful of which can detect the echo of another merchant ship at 20 miles, pretty good for Astra’s comparatively low height.

She is also fitted with an AIS ‘A’ unit and has her own continual satellite link to monitoring equipment ashore. This allowed our shore team and close family and friends to monitor our progress.

After passing Robinson Crusoe Island 150 miles away on our port side, the International Space Station orbiting 220 miles above the earth was our closest contact to humanity for over 3,000nm until we reached the British island cluster of Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oero.

The wave analyser shows the pattern of waves approaching the boat

When I was growing up on Barra, my grandparents had a polished wooden pigeon hand carved with the inscription ‘Made by …. who is a descendant of Fletcher Christiansen, Pitcairn Island’.

My father had sailed there in the early 1960s and had traded a can of condensed milk for it. Sadly, Pitcairn is not able to deal with refuelling a boat of Astra’s size so my opportunity to trade was curtailed!

During this long leg across the Pacific, between the meridians of longitude of 076°W and 124.5°W (a distance that takes about 16 days) we were in a VSAT black spot.

The satellite communication signal starts to fade.

We had not been prepared for our first VSAT black spot in the South Atlantic. This time we were ready for it and put low availability measures in place before we got there so that we could continue our essential communications with agents and our DPA using our back-up Fleet Broadband system.

This is rated at just 64-128 kbps, compared to 2,048 kbps for VSAT, so is only suitable for basic tasks. Our other back-up was an independent hand-held satellite phone and an MF/HF radio.

Thankfully, the weather proved largely kind with winds of Force 3 and 4 from astern. After some initial squalls, the afternoons became very dry and hot and we settled into a more structured routine – the exercise bike proved to be an inspired purchase, with almost all of us doing between 15-20 km per day.

With such fabulous conditions we had the chance to brush-up on our celestial navigation skills taking morning and evening stars when cloud cover permitted and Meridian Passage to give us our latitude at true noon.

Day 72: 10 Feb

Today we reached the half-way point across the Pacific, 2,200 miles from either port, and shortly afterwards we transferred the final 6,000 litres of fuel from our deck tanks to our main tanks.

After another dogleg adjustment for weather, we were able to increase speed in increments while carefully monitoring our fuel consumption. This allowed us to achieve speeds of over 9.75 knots on the final five days into Tahiti.

Astra arrives in Teahuppo, Tahiti after their 21-day crossing

As a result we arrived in Tahiti just 21 days after leaving South America at an average speed of 8.56 knots. We had 4,410 litres left, about 10% more than my conservative calculation, so had averaged 8,200 litres per 1,000nm.

Considering the first 2,950nm leg of our circumnavigation, from Lanzarote to Saint Helena into the NE Trade Winds took us 20 days, we wouldn’t have believed that this 4,400nm leg would be completed in 21 days.

It was another big challenge surmounted on our way to becoming the first sub-24m motor boat to circumnavigate the globe via the southern capes but plenty more challenges still lay ahead…

First published in the June 2022 issue of MBY. Next month: Iain completes his Pacific passage in Australia.